The gold rush at Gabriel’s Gully near Lawrence in 1861 brought thousands of hopeful prospectors into Otago from other parts of New Zealand, the Australian diggings and even further afield. In the second half of 1861 Otago’s population rose from less than 13,000 to more than 30,000.

Men poured out of Dunedin to different fields to try their luck. The shortest route from Dunedin to the Lawrence area was via West Taieri (Outram) and the Maungatua mountain into the Upper Waipori valley, across the river and along the leading ridge before dropping down to Gabriel’s Gully and surrounding areas. It was natural that when making this journey people paused to look for gold in creeks along the way.

The first Waipori settlement

Gold was discovered at Waipori on 17 December 1861, when a digger named O’Hara and his party found gold in the upper Waipori Valley along Lammerlaw Creek, a tributary of the Waipori River. The Waipori rush was on.

Just three days after the discovery a constable reported 400 miners working on the banks of Lammerlaw Creek, and soon after a town of tents and stores had formed. Considerable quantities of gold were being removed.

(Otago Daily Times 21 December 1861)

By February 1862 it was reported that a growing settlement contained seven stores, including bakeries and butchers. The settlement was located on a small site perched on a couple of hills, hard to access and in winter it would become cut off from the main mining areas.

The second Waipori town

By the winter of 1862 the township had relocated a few miles away to the junction of the Waipori River and Lammerlaw Creek, where the river could be forded and a footbridge was built. First called Waipori Junction to differentiate it from the original settlement, it soon became known just as Waipori as the original site was vacated.

The town grows

By 1865 it was reported that “Waipori is attracting a great deal of attention, and its magnificent resources are now for the first time being gradually developed”. The population of the goldfields was then about 1,000.

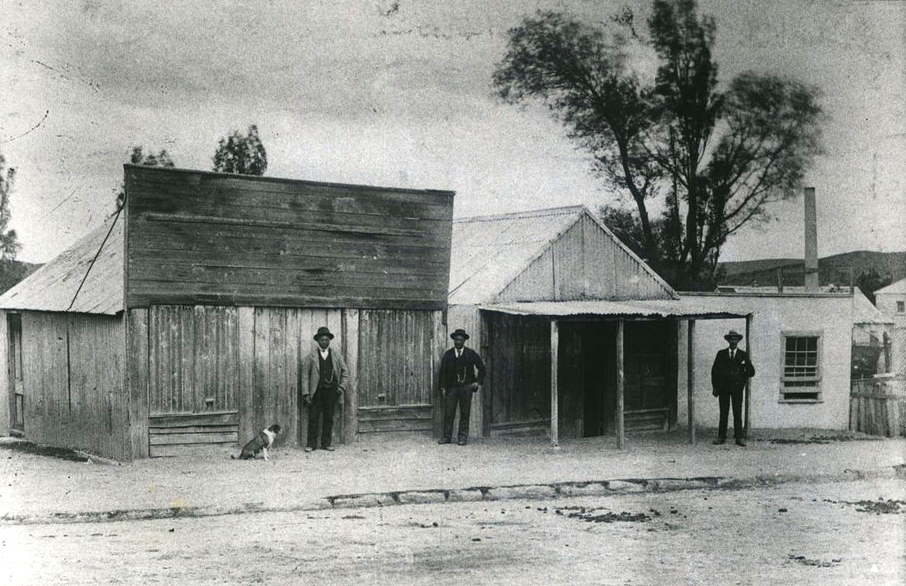

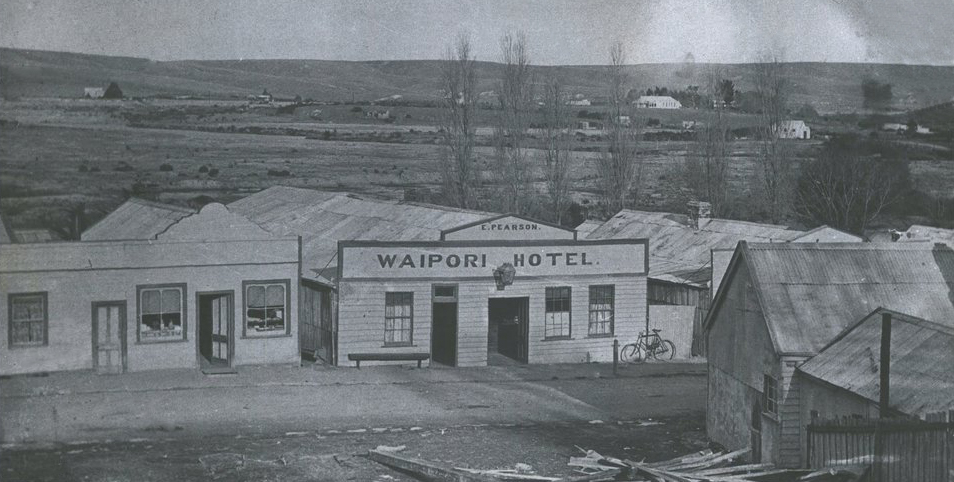

The new Waipori town grew as streets were formed and businesses set up. There were no fewer than 11 hotels (and three ginger beer manufacturers for those of more restrained habits). There were general stores and specialist stores including, over the next few years, bakers, butchers, greengrocer and a draper.

There were service providers including blacksmiths, bootmakers, carpenter, funeral director, signwriter and even a hairdresser. Bullock wagons brought supplies in, and coach services took passengers and mail to and from Waipori.

A school was started and churches established. A permanent police presence kept the peace, maintained law and order and guarded gold shipments.

The town was the focus for the surrounding goldfield district and contained all the services that a small frontier community needed or could provide.

Fluctuating fortunes

Waipori was at its peak in the mid-1860s, and from then its population fell and rose again in line with success on the goldfields. Waipori saw many innovations in quartz mining, sluicing and dredging — either early use of new techniques from overseas or in some cases leading the world with patented mining inventions.

One example was dredging, which brought new life and new people to Waipori in the 1890s. The population that was starting to dwindle as alluvial claims became uneconomic for lone miners increased as engineers and dredge masters arrived in the district. Local men became dredge hands and wives ran boarding houses for the growing population. Waipori businesses thrived.

In total about 17 dredges operated on the Waipori River, but they didn’t last long. Many went out of business in the first decade of the 1900s, and the final one fell silent in about 1914.

Global war

Mining activity had dwindled by the time the First World War broke out in 1914. Many men from the district were enlisted in the armed forces, and some did not return. Their stories are told here.

A typical pioneering town

Waipori followed a trajectory typical of many towns in early New Zealand, whether established for goldmining or to chase other resources. Establishment, growth and the development of a thriving and supportive community were eventually followed by decline and abandonment.

After the First World War many men returning from military service moved to opportunities outside the Waipori district. Gold-mining dwindled away to a few hardy men working their claims. Sheep farming became more important for the economy of the district.

Rather than fade away to a ghost town like many settlements built on gold, Waipori’s end in the 1920s was much more abrupt.

The town is flooded

The Dunedin city corporation (later council) had built a small hydro dam at Waipori Falls, where the Waipori River rushes through a narrow gorge just inland from where Dunedin airport is now. The site had huge potential for hydro generation, and in 1920 and 1924 the council gained the powers to build a high dam that would create a lake flooding the Waipori Flats, including the township and much of the goldfield.

From 1921 the council began purchasing the mining rights and leases from miners or their families, and paid compensation to landowners and miners for the land, mining rights and equipment that was to be destroyed by the new lake.

At a large conference at Waipori over two days in March 1924 the amounts of compensation were agreed by the owners, miners, Dunedin city officials and central government officials. The 25th of March 1924 was known as ‘Settlement Day’.

(Evening Standard 25 March 1924)

The population continued to dwindle. By September 1924 a newspaper reported that the town was all but deserted, while a few miners lived in the area continuing with their claims. Compensation was paid to these last few hold-outs from 1925 to 1928. Dams were built in 1924, 1931 and 1949, forming Lake Mahinerangi and progressively raising it to its present level.

Some mining artefacts remain, and the cemetery is preserved above the lake shores. Only one original house, that of Herbert (Bert), son of the pioneer lessee of Waipori Station Robert Cotton, and Bert’s wife Flora, has escaped the flooding and still stands.